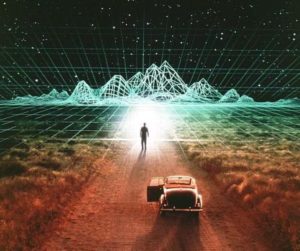

Douglas is standing beside his car, mesmerized, gazing into the distance, trying to grasp what his eyes are seeing. His phone rings: “Where are you?” He answers in a flat monotone, struggling to control his mounting panic: “You could call it the end of the world.”

This is my favourite moment of The Thirteenth Floor. We, the audience, appreciate the bitter poignancy of his words. The world as he knows it has indeed come to an end, but there is also a deep irony in the statement: he is staring ahead not at a road meandering towards the mountains in the far distance but at a green wire-frame horizon. He has discovered the literal edge of his reality. At that moment he understands that everything is a computer model: his world, his universe – and himself!

Sadly, the critics were not enthusiastic about The Thirteenth Floor. They compared it unfavourably with The Matrix, which had been released two months earlier. Admittedly, The Matrix, with its thrilling visual effects and action scenes, including liberal use of “bullet-time” photography and “wire-fu” martial-arts sequences, was an altogether more polished movie than The Thirteenth Floor. Nevertheless, I was unprepared for the disproportionate number of critics who wrote ecstatically about the underlying philosophy of The Matrix while at the same time remaining lukewarm or even scathing about The Thirteenth Floor.

I felt this was quite unfair. The Matrix uses the “brain in a vat” scenario, where billions of human beings are kept in liquid-filled vessels with their brains connected to a simulated world (the Matrix). Because these brains’ normal connections to their sensory organs (eyes, ears and so on) have been usurped by cables that connect them to the Matrix, these people have no way of telling that what they perceive is not real. This, the critics pointed out excitedly, echoes the musings of philosophers from Descartes and Plato to modern philosophers such as Hilary Putnam and Jean Baudrillard.

However, The Thirteenth Floor is based on a far more subtle premise. Rather than have its characters being only one broken cable connection from waking up into reality, in this movie, the whole universe is a computer simulation.

In fact, the theme of the movie is even more subtle than that, because, in the late-1990s laboratory in which Douglas works, there is a computer that, itself, is running a simulated universe, manifest as Los Angeles in 1937. So, we have a simulated universe (1937 Los Angeles) nested in a simulated universe (late-1990s Los Angeles) nested in the universe that runs the late-1990s Los Angeles universe, like Russian dolls. (Those who have watched the last scene of the movie will realize that even the “top” universe, in the year 2024, is probably also a simulation, as suggested by the movie suddenly ending in a blank screen with a single bright line across the middle, like an old CRT television set being switched off.)

If you managed to struggle to the end of the Plexus page Self-Awareness in a Toy Universe, you will see that I tried to make the point that the self-awareness of the UTMs in the Ants is not due to the actual running of the Game-of-Life programs but is contained within the pure mathematical structures of these programs. In other words, the UTM in the Game of Life does not spring into self-awareness when the program is started up: the self-awareness of the UTM is a property of the pattern of the particular Game-of-Life block universe in which it finds itself. Its self-awareness is completely independent of the simulation, which has no self-awareness.

This led me to an alternative definition of reality: Reality within a mathematical structure is the complete definition of that structure. Plugging this back into the Plexus hypothesis then leads, eventually but inexorably, to the conclusion that the reality that we experience in our universe is only part of a higher reality that we cannot experience directly! I even named this higher reality a super-reality!

Immediately, the red flags went up! If I submitted a paper with “super-reality” in the title, it would bounce back faster than a Zectron Super-Ball from a concrete wall. So, I tamped down the title and submitted it to the same science-philosophy repository mentioned in my earlier post, The Cathedral of Learning: the PhilSci archive hosted by the University of Pittsburgh. I called the paper “Levels of reality: emergent properties of a mathematical multiverse”. You can read the full text here: PhilSci.